The Swiss Mount Everest/Lhotse Expedition 1956

Excerpt from: Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research 1939 to 1970. Published in Zurich 1972

Participants: Albert Eggler, expedition leader; Wolfgang Diehl, deputy leader; Hans Grimm; Hansrudolf von Gunten; Fritz Luchsinger; Jürg Marmet; Ernst Reiss; Dölf Reist; Ernst Schmied; Eduard Leuthold, expedition physician; Fritz Müller, geographer and glaciologist.

Results: Second ascent of Mount Everest (8850 m), first ascent of Lhotse (8501 m). Glaciological and meteorological observations of the Khumbu glacier region.

After the second Everest expedition returned in 1952, the Foundation asked for permission to conduct a third expedition. Othmar Gurtner drew up the plans for this effort. In September 1953 (after Everest had been climbed for the first time), the Nepalese government gave the Foundation permission to carry out research across the whole of the Everest massif throughout the year 1954. Shortly thereafter, it was announced that an expedition from the «Daily Mail» had received permission to explore the Khumbu glacier region to find the legendary «Yeti». This was the same area that the Foundation had planned to research, and it therefore decided to cancel its expedition for 1954. In 1955 Dyhrenfurth Senior and Junior applied to climb Lhotse. Once again, this expedition was in competition with the Foundation’s plans, which were therefore renounced for 1955. The Dyhrenfurth expedition was forced to turn back after having reached a height of around 8,100 metres on Lhotse, but it did bring back the documentation on which Erwin Schneider’s maps of Mount Everest were based.

The Foundation then started working on a new project for 1956. Changes were made to the 1954 plans, which were mainly intended to serve the aims of scientific exploration. Instead, the Foundation outlined a mountain-climbing expedition involving a team of first-class mountaineers. The aim was to climb Everest for the second time, and Lhotse for the first time. Less emphasis was placed on the scientific aspects.

In December 1955, the Foundation published an appeal for a national subscription scheme.

The expedition had a total budget of 295,000 Swiss Francs (the actual cost was 360,000 Swiss Francs). The money was raised, and various companies made generous donations of deliveries in kind. The expedition was officially named the “Schweizerische Mount Everest-Expedition 1956”.

The ideal leader for the expedition was found in Albert Eggler (43). As leader of the mountain troops and a veteran of AAC Bern, Eggler already knew the other candidates personally: Ernst Reiss (36), an aeroplane mechanic from Brienz, had already been on the South Col of Everest in 1952; Jürg Marmet (29), born in Spiez, was a trained mountain guide, chemist and oxygen specialist living in Zurich. The core of the future expedition had already been formed by this trio in the spring of 1955. The Foundation sent a letter to around 20 of the best mountaineers in German-speaking Switzerland in order to recruit the rest of the expedition. The following members were selected from the large number of applicants: Dölf Reist (35) from Interlaken, aeroplane mechanic and photographer (part of Reiss’s rope team); Fritz Luchsinger (35), instructional officer in Thun, also part of the rope team with Reiss and Reist; together, the three formed an outstanding Berner Oberländer rope team; Wolfgang Diehl (48) from AAC Bern, a lawyer and Greenland specialist with extensive Alpine experience; he was the senior member of the expedition and acted as deputy leader; Hansruedi von Gunten (28), a chemist, also from AAC Bern, and his brother-in-law Ernst Schmied (32), both «apprentices» to Diehl. These three also formed an excellent rope team. Hans Grimm (44), a dentist from Wädenswil, was also an experienced mountaineer; Fritz Müller (30) from Zurich, geographer and glaciologist, accompanied the team as an independent scientist; at the last minute, Eduard Leuthold (28), a doctor from Zurich, was found to accompany the climbers as the expedition’s physician. He was certainly given the chance to prove his worth. The composition of the entire team was very homogeneous. They completed a military mountaineering course in summer 1955, followed by avalanche and explosives training in January 1956. They prepared themselves thoroughly and in every respect for the challenge ahead. As the strategist of the group, Eggler developed a precise operational plan. The approach to Everest would have to take place between May 20 and June 10. According to meteorological records, the last week in May would be the best time to attempt climbing the Eight-Thousanders in Nepal. The entire journey, including the timetable, loads and number of necessary carriers, was planned with these dates in mind. Marmet recommended using a lighter French oxygen tank (light Makahn model), featuring open circulation and an improved mask, which Marmet simplified even further. The team took 22 units, which proved their worth extremely well. The entire unit weighed 6.6 kilograms, much lighter than the devices used by the 1952 expedition, which weighed 14.2 kilograms.

The first team of six participants sailed from Genoa to Mumbai (Bombay), where they were delayed for a full week by customs officials. From there, they travelled by train to Patua. Eggler and Müller flew directly to Delhi to get visas for Nepal, and then on to Katmandu, where they obtained a special visa for Lhotse. In Nepal, climbers usually only receive permission to climb one mountain. Luckily, all of these formalities were organised without difficulty. The team hired an excellent liaison officer to assist in these efforts; a student named Prachand Nan Singh Pradhan. On March 2, the entire group gathered in the border town of Jaynagar, with the exception of Grimm and Marmet, who joined them later with the oxygen supply. Sirdar Pasang Dawa Lama joined the team here, with 22 Sherpas from Darjeeling. The entire group then started off with buffalo carts on the familiar path to Chisapani. From there, they continued onwards with 350 porters to Thare-Jubing and then Namche Bazaar, where the team set up base above the village on March 21. About 20 cm of snow fell the next day. The five-hour march to the monastery settlement of Thangboche followed on March 24. Only 150 porters were still with the group, and it was necessary to organise additional support. Everything had gone well up to this point, but then Luchsinger became ill with acute appendicitis.

The Lama, or abbot, of the monastery in Thangboche provided a room for the sick climber. Unfortunately, this room lacked one very important quality: heat. Luchsinger’s condition seemed critical at times, leading to considerations of an emergency operation. In the end, the young expedition doctor, Eduard Leuthold, proved his abilities by achieving success with treatment based on medication. Shortly thereafter, Wolfgang Diehl began to show signs of a lung infection following a training stint. This was cured successfully using intensive oxygen treatment. Finally, the Sirdar of the expedition, Pasang Dawa Lama, was unable to continue because of a high fever. Leuthold accompanied him to Namche Bazaar, where he recovered. Pasang’s brother-in-law, Dawag Tenzing, proved to be an outstanding replacement.

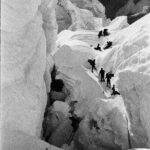

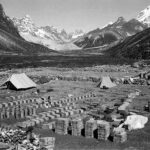

During the acclimatisation phase, the team climbed several less challenging mountains, as well as a few un-named five-thousand-meter peaks. Base camp (5,370 m) was set up on April 7. From there, the expedition set off to conquer the famous Khumbu icefall. The team did not experience any difficulty as far as Camp I (5,800 m) in the hollow of the glacier. The problems started to appear on the way to Camp II (6,110 m) at the start of the Western Cwm, the most dangerous part of the icefall. The large lateral crevasses were at least four meters wide, and the team managed to get across using two light metal ladders bolted together. Several ice blasts were necessary to make the way secure. Camp III (6,400 m) was developed as a forward base.

On May 1, the team built Camp IV (6,800 m) on the lowest terrace of the Lhotse Face. Luchsinger had recovered from his appendicitis and rejoined the team here. Camp V (7,400 m) was set up on a terrace below the «Yellow Band» on May 6. From here, a cross path was created using rope railings, as an access to the lower station of a rope winch lift in the Lhotse Face. The upper station was located near Camp VIa, under the «Geneva Spur». While the rope winch was in use, the weather conditions worsened and it started to snow. Luchsinger and Schmied, who were at Camp VIa, decided to climb down to Camp V, but it became necessary to leave Camps V and IV for a period of time due to the continued snowfall. The weather cleared up again on May 14, but strong winds covered the tracks of the group, making it necessary to clear the path to Camp VIa and onto the «Geneva Spur » over and over again. On the evening of May 17, Reiss and Luchsinger were at Camp VIa, Reist and Gunten at Camp V, Eggler and Schmied at Camp IV and everyone else at Camp III.

The surprise attack on Lhotse

After a cold night (-25° C at Camp V), Ernst Reiss and Fritz Luchsinger started their approach to the summit of Lhotse (8,501 m) on May 18 and crossed into the Lhotse couloir. They reached the crux around noon, and managed to overcome it using pitons. Six hours after leaving Camp VIa, the two climbers had reached the jagged peak of Lhotse. They stood in the sun on the sharp summit for forty-five minutes. With no place to sit, they had to be especially careful when taking photographs from the peak. The view onto the jagged, desolate ridges of Lhotse and over to Everest was of a magnificent wildness. Their oxygen was used up, the winds were getting stronger, their hands and feet were becoming numb – it was high time to come down. The climbers carefully edged their way down the extremely steep and exposed slopes of fresh snow, moving one at a time. The large traverse brought them back to Camp VIa. At 6:15 p.m., the two stood exhausted and happy before their empty tent, which had collapsed under the snow. After shovelling out the tent, they ended their tough 12-hour day by crawling inside and into their sleeping bags. Next day, they climbed down the mountain, stopping at Camps V and IV before reaching Camp III, where they quickly recuperated.

The ascent of Lhotse meant that Swiss mountain climbers had reached the summit of an Eight-Thousander for the first time ever.

The ascent of Everest

On May 21, Camp VIa was moved over the «Geneva Spur» (8020 m) to the South Col (7,986 m). The new Camp VIb was located approximately 100 metres west of the camp set up by the 1953 British expedition. Here, our climbers found many useful items, edible food rations and oxygen cylinders. On the afternoon of May 22, following light snow in the morning, the first rope team set off for the summit: Ernst Schmied and Jürg Marmet with four Sherpas.

The climbers used oxygen in their ascent. After two hours, the team reached the 8250 m point, where Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing set up their highest tent camp in May 1952. At around 8,400 metres, west of the ridge edge, they found a small depression that was suitable for a tent camp. The four Sherpas were sent back to Camp VIb while Schmied and Marmet set up Camp VII with a small two-person tent. Because of the strong winds, the tent had to be weighted down with stones and fixed using pitons. Both climbers were well equipped, with an air mattress, a double sleeping bag made of down, a joint bivouac sack made of nylon, a small stove, a summit package full of necessary provisions and five full oxygen cylinders. During the night, the heavy snow weighed the tent down so much that the climbers had to uncover it to avoid being suffocated. They had to wait until 8:30 a.m. to start their approach. The weather was still very stormy, which made the team doubt their chance of success. However, the winds gradually calmed down, and the two climbers reached the top of the South Summit (8,760 m) at about midday. A ridge of loose limestone with massive overhanging snow cornices led to the main summit. The weather had finally cleared up, revealing clear blue skies. A steep 15-metre-high stage challenged the climbers just below the summit, with a spur leading up between rock and snow. Schmied worked his way up step by step, followed closely by Marmet. At 2:00 p.m. on May 23, people stood on the highest summit on earth for the second time. Schmied attached the flags of Nepal, Switzerland and Bern to his ice pick, while Marmet’s camera recorded pictures of the unique panorama. The winds were calm, allowing them to take off their oxygen masks and stay on the peak for nearly an hour. Then they were suddenly surrounded by dense fog, forcing them to make a fast descent. At 5:00 p.m. they reached Camp VII, where they found the second team of Dölf Reist, Hansruedi von Gunten and a Sherpa busy shovelling out the snow-covered tent. The Sherpa accompanied Schmied and Marmet on their rope, and they continued down to the South Col, reaching Camp VIb shortly before 7:00 p.m.

The second team of Reist and von Gunten were also successful in reaching the summit. The night was very cold once again, but the next day, May 24, was the most beautiful and calm day of the past several weeks. The team began their approach at 6:45 a.m., enabling them to enjoy a short rest at the South Summit. When they approached the traverse to the main summit, with the cornices that looked so treacherous, they found clear tracks left by Schmied and Marmet. They were even able to follow the steps of their predecessors at the steepest point of the climb, and reached the summit at 11:00 a.m. The weather was bitterly cold but absolutely still. The team rested at the summit for two whole hours, taking off the oxygen masks from time to time. Large clouds approached from the south, indicating that the monsoon would arrive before long. The climbers descended in great shape and record time, reaching the South Col, lying almost 1,000 metres below, just two hours later, at 3:00 p.m.

After some hesitation, Eggler decided not to send another rope team to the summit. The monsoon was approaching, and it seemed wiser and more sensible to descend. Luchsinger, Reiss, Müller and Leuthold climbed to the South Col, and then the entire team started their descent to base camp, where everyone arrived in a healthy condition on May 29. The great adventure had thus come to an end.

Apart from the couple of cases of illness suffered during the approach, this expedition had enjoyed excellent luck, especially with regard to the rare good weather. However, the main reason for the success of the expedition was the careful organisation, competent leadership and (most of all) the good will and cohesion within the entire team. This was one of the most successful expeditions in the history of the Himalayas. It also marked the positive conclusion of a program to which the foundation had devoted five long years of hard work.